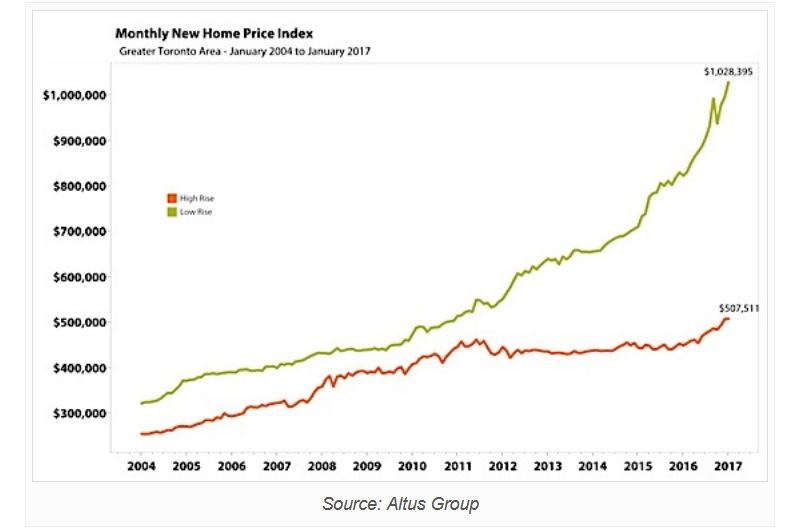

The gap between the average costs of newly built low-rise and high-rise homes in the GTA got wider again in January, 2017. A brand-new single-detached house now costs twice as much as a stacked townhouse or condominium: $1,026, 395 to $507,551. The single-detached cost is up 25 per cent compared to a year ago; the condo cost is higher by 13 per cent.

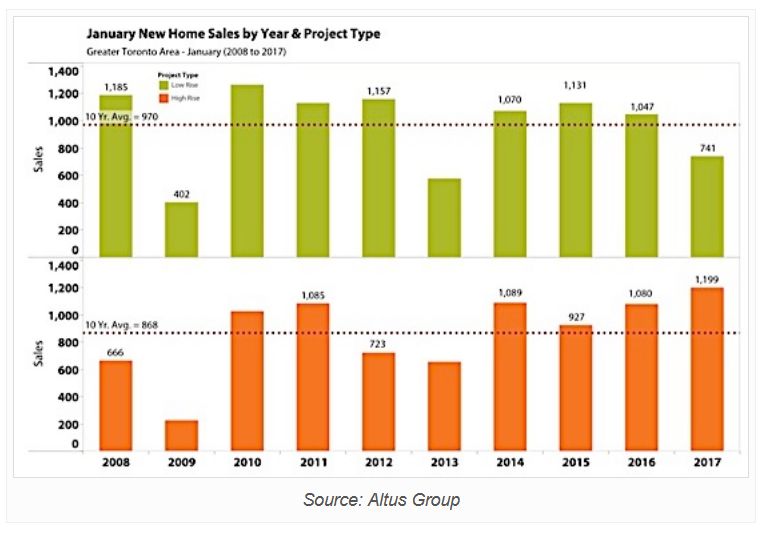

Not merely prices but numbers of sales are diverging also. New low-rise dwelling sales were down in January, with just 741 brand-new homes sold, a decline of 29 per cent from a year ago. In Toronto, only thirty-three brand-new low-rise homes were sold in January. New condo sales went the other way, rising 11 per cent, according to data provided by Altus Group for the Building Industry and Land Development Association (BILD).

Inventory of homes available for sale in both categories was also down, in the event of its low-rise homes to a record low, with just 1,524 ground-related homes for sale. The number of brand-new condominiums for sale, though still relatively high with 11,529 units available, was nonetheless at its lowest in ten years.

Condominiums now make up 88 per cent of available inventory , noted BILD CEO Bryan Tuckey, who added that the GTA faces a “severe” deficit of housing inventory, with less than half the available inventory today than existed 10 years ago. Tuckey has frequently said that the acute shortage of inventory, which is driving prices ever higher, is due to the lack of “serviced, developable land, excessive red tape and frequent defers of new developments permission process .”

Our industry is implementing provincial plan by building more condominium apartments and less ground-oriented housing. A decade ago condominiums represented just 42 per cent of available inventory compared to 88 per cent in 2017.

Many agree with this analysis, including the Ontario Real Estate Association( OREA ). That organisation’s CEO, Tim Hudak, listed five steps the Ontario government could take to alleviate the housing inventory problem in the GTA. One of these would be to give municipalities more flexibility so that builders can build the kind of housing that people want, rather than staying to “one-size-fits-all” growth plan.

Another positive step, Hudak argues in a piece in the Toronto Star, would be to address the “missing middle” of housing inventory. Rather than let the polarisation of housing choice to continue — high-rise condo or single-family home — allow for such options as laneway housing, stacked apartments and mid-rise structures in areas that now restrict these types of housing. And it almost goes without saying that Mr. Hudak wants to see approvals process speeded up, unnecessary defers eliminated.

Economists agree that the government’s growth plan, which emphasises intensification rather than outward growth, has had an impact on the inventory of available low-rise homes in the GTA, particularly as some older homes in low-rise home areas being torn down and redeveloped as condominiums. However, Robert Kavcic, senior economist at BMO, believes that the city is not running out of land, citing Neptis Foundation estimates that there is enough land available to support fifteen more years of outward, land-related growth.

Greenbelt and smart growth preacher Erin Shapiro argued in a blog for Environmental Defence that the “real reasons” being responsible for rising housing prices are low interest rates, demand for city central areas, absence of housing options and lack of rental properties. Shapiro insists there is no deficit of available land available for developing, and asks the issues to, if developers are so concerned about affordability, “why is the majority of suburban development in the form of enormous homes selling at high prices?”